ARE YOU POSITIVE . . . OR FALSE POSITIVE? IMPROVING YOUR INTERPRETATION OF THE EFAST EXAM

/THE CASE

A 25 year old female presents as a trauma activation after a motor vehicle accident. EMS reports the patient was the belted passenger of a motor vehicle which sustained a passenger side impact versus a tree at 25 mph. The airbags did not deploy, the patient did not lose consciousness, and she did not self extricate. Initial vitals were HR 100, BP of 126/80, RR 22, and SpO2 96% on room air. The patient is complaining of right arm pain and is noted to have a grossly deformed and open right distal forearm fracture.

WHAT’S YOUR NEXT MOVE?

In the chaos of the critical care bay you force yourself to march through ATLS. The patient’s primary survey is unremarkable - her airway is patent, breath sounds are equal bilaterally, she has strong femoral pulses and no external evidence of hemorrhage. Repeat vitals are HR 105, BP 130/74, RR 20, SpO2 97% on room air. GCS is 15.

The secondary survey doesn’t give you any big surprises. You, of course, note the open right distal forearm fracture. The patient has a very minimal amount of diffuse abdominal tenderness with no external evidence of injury. The secondary survey is otherwise unremarkable. Concerned about the patient’s diffuse abdominal tenderness and tachycardia, you decide to do a FAST exam …

What is the FAST exam?

We know this ultrasound study well. The FAST exam, or Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma, is one of the most common applications of point of care ultrasound in the Emergency Department. The goal of the FAST exam is to detect free fluid in the abdomen, typically hemoperitoneum in the unstable trauma patient. The “extended” (E)-FAST exam also looks for pneumothorax, pleural effusion and pericardial fluid. The EFAST exam can quickly evaluate the unstable trauma patient and direct emergent management of hemoperitoneum, hemopericardium, hemothorax, and pneumothorax.[1]

To evaluate for free intra-abdominal, pleural and pericardial fluid, the following views are obtained using the curvilinear probe. Free fluid characteristically has sharp edges and will dive between structures, as seen in the clips below.

Green dot indicates orientation of marker on probe

Right Upper Quadrant

Look for free fluid in Morison’s pouch between the liver and kidney, around the inferior liver tip, around the inferior pole of the kidney, and between the liver and the diaphragm. Then visualize the diaphragm and spine; the spine will be visible above the diaphragm only if pleural fluid is present.

Right upper quadrant ultrasound with no free fluid

Right Upper Quadrant Ultrasound with free fluid in the hepatorenal space

Right upper quadrant ultrasound with pleural effusion visualized in the right chest and a positive “spine sign”

Left Upper Quadrant

Look for free fluid between the spleen and kidney, inferior aspect of the spleen, and between the spleen and the diaphragm. Then visualize the diaphragm and spine; the spine will be visible above the diaphragm only if pleural fluid is present.

Left upper quadrant ultrasound with no free fluid visualized

Left upper quadrant ultrasound with free fluid at the inferior aspect of the spleen extending into the splenorenal space

Suprapubic

Look for free fluid adjacent to the bladder. It is essential to fan through the entirety of the bladder in a transverse and longitudinal axis.

Suprapubic ultrasound through the bladder in transverse orientation with no free fluid visualized

Suprapubic ultrasound through the bladder in longitudinal orientation with free fluid visualized deep to the bladder

Evaluate for Pericardial Effusion

Subxiphoid: The curvilinear probe is placed inferior to the xiphoid process, angled towards the patient’s left shoulder with the probe flattened to provide a view into the chest. The hyperechoic pericardium is visualized; pericardial effusion will appear as a hypoechoic line between the pericardium and the myocardium.

Subxiphoid ultrasound of the heart with no pericardial effusion seen

Subxiphoid ultrasound of the heart showing pericardial effusion

Parasternal: If a subxiphoid view does not provide an adequate view, a parasternal view can be obtained using the phased array probe. Place the probe just to the left of the sternum and slide up and down until you visualize the heart between the ribs.

Parasternal long axis ultrasound of the heart with no pericardial effusion seen

Parasternal long axis ultrasound of the heart showing pericardial effusion

To evaluate for pneumothorax, place the curvilinear or linear probe in a longitudinal orientation along the anterior chest wall. Visualize the pleura between rib shadows. Absence of pleural sliding--the “shimmering” or “ants marching” appearance - is characteristic of a pneumothorax.

Curvilinear probe on the anterior chest with lung sliding seen

Linear probe on the anterior chest with no lung sliding seen, characteristic of pneumothorax

BAck to the case . . .

You quickly perform an EFAST on your patient, with the following images obtained below.

Right Upper Quadrant Interpretation: No free fluid in the RUQ abdomen or chest

Left Upper Quadrant Interpretation: No free fluid in the chest… but what’s that next to the spleen?

Suprapubic Interpretation: No free fluid in the pelvis; uterus is seen at the end of the clip

Parasternal Long Axis View of the Heart Interpretation: No pericardial effusion

Right Anterior Chest Interpretation: No pneumothorax

Left Anterior Chest Interpretation: No pneumothorax

What’s the deal with that LUQ view? Is that a splenic laceration?

There is a thick walled, heterogeneous filled structure in the anterior field of the LUQ view which does not persist with posterior fanning. This is characteristic of the stomach and its gastric contents - NOT a splenic laceration!

Case Resolution

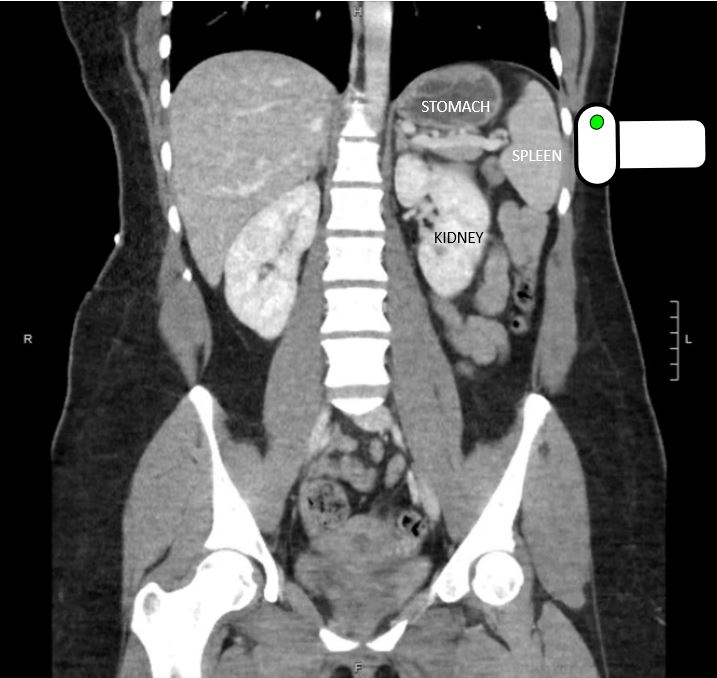

Based on the mechanism of injury, patient’s diffuse abdominal tenderness, and distracting injury, you ordered a CT scan of the patient’s chest, abdomen, and pelvis to assess for intrathoracic and intra-abdominal injury. This revealed no evidence of acute traumatic injury in the chest, abdomen, or pelvis. The stomach was, of course, visualized on CT with a similar appearance to what you saw on your bedside ultrasound:

Left upper quadrant ultrasound with stomach and gastric contents visualized next to the spleen

CT of the abdomen and pelvis in coronal plane showing the stomach filled with gastric contents adjacent to the spleen

anOther EFAST Fake-Out

In addition to visualization of gastric contents in the LUQ, there is another common FAST exam finding that can be easily confused with a positive exam: the double line sign.

The double line sign refers to the appearance of a perinephric fat pad (especially in the RUQ), which can easily be misinterpreted as free fluid in Morison’s pouch. Both perinephric fat and free fluid will appear as hypoechoic structures separating fascial planes. However, only a perinephric fat pad will have hyperechoic lines both superficial and deep to the hypoechoic structure - hence the double line sign. These double lines are fascial planes that are visible because of perinephric fat. The double line sign is present in at least 30% of normal exams. There doesn’t appear to be a correlation with BMI, although age does seem to increase the incidence.[2,3]

In contrast, when free intraperitoneal fluid is present, only one echogenic line will be visible bounding the fluid. Pathologic free fluid does not highlight fascial planes, unlike perinephric fat. Compare the two clips below:

Right upper quadrant view of the FAST exam showing the double line sign, indicative of perinephric fat between the liver and kidney

Right upper quadrant view of the FAST exam with free fluid seen between the liver and the kidney; no double line sign is seen

This case demonstrates how tricky the EFAST exam can be. In the stressful situation of managing an acute trauma patient, take the time to obtain adequate views as described above.

Remember that free fluid characteristically has sharp edges and will dive between structures; it does NOT have smooth edges and walls like physiologic structures (such as vasculature).

Be aware of the double line sign and appearance of the stomach on ultrasound so that you don’t call false positives.

Ultimately remember that the EFAST exam is a rule-in test, not a rule-out test - it can rule in free fluid and pneumothorax, but a negative EFAST exam doesn’t rule out injury. If you are concerned about an intrathoracic or intra-abdominal injury in a trauma patient in spite of a negative EFAST exam, proceed to comprehensive imaging with CT!

Written by Evan Gill, MD & Randy Kring, MD

Edited and Posted by Jeffrey A. Holmes, MD

References:

1. The American Institute For Ultrasound In Medicine. (2015). Focused Assessment With Sonography in Trauma (FAST) Examination. Retrieved from https://www.aium.org/resources/guidelines/fast.pdf

2. Patwa, A.S. et al.Prevalence of the “Double-Line” Sign When Performing Focused Assessment With Sonography For Trauma Exams. Intern Emerg Med. 2015 Sep;10(6):721-4. [Pubmed]

3. Sierzenski et al. The double-line sign: a false positive finding on the Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (FAST) examination. J Emerg Med. 2011 Feb; 40(2): 188–189.[Pubmed]