Coding in the Community

/Tired of reading? Prefer to absorb your MedEd through your wonderful powers of hearing? Check out our podcast HERE

Thank you for joining us for our discussion on how to code patients well in the community setting. In this blog and podcast interview we touch on some overarching topics of cardiac arrest management, but cater the discussion to issues, obstacles, and dynamics within the community. Our special guest for this post is Dr. Salim Rezaie from R.E.B.E.L EM.

The Two Pillars of Cardiac Arrest

If there is a take home from this post, it is that there are only two things proven to save lives in cardiac arrest (when you look at the literature) and those are:

1) High Quality CPR with minimal delays

(Check out our video on high performance CPR by Dr. Mike Bohanske)

2) Timely Defibrillation

The Delays

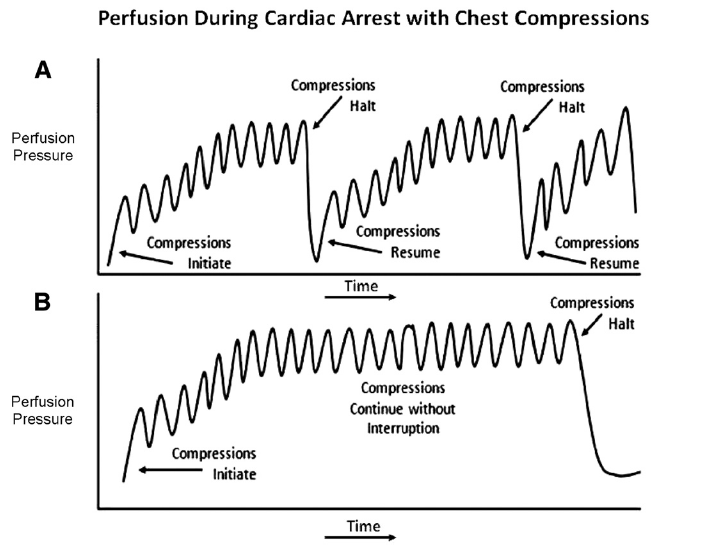

Anything that distracts from these two elements of the resuscitation is a detriment to the patient. As you can see in the graphic from Cunningham et al [1] each pause in compressions leads to a loss of coronary perfusion pressure, which takes time to regain. The areas where we commonly see the greatest delays are:

Waiting on defibrillator charge

CPR should continue until the defibrillator is fully charged. Then and only then should a rhythm check occur. This helps you catch your ischemic myocytes at the highest chance of electrical conversion to an organized rhythm.

Note that this is a rhythm check, checking for a pulse when the patient is clearly in ventricular fibrillation is not valuable and wastes precious time. If a possibly perfusing rhythm is seen, attention can be put toward checking for a pulse. That is not to say that a finger on the femoral artery while dedicating your attention to a rhythm analysis is a bad idea. As you see below, things can happen in tandem.

Airway

Focusing on the airway at the expense of CPR is bad practice. One example of this paradigm shift is the latest AHA recommendations, which moved from ABCs to CAB - circulation (ie CPR) first.[2]

Point of Care Ultrasound (POCUS)

Taking too much time with POCUS is our third major slip up. We all want to get that ideal view of the heart, and in a code that can be difficult. We are taking too long to find our view and review the images in real time. This leads to long pauses in CPR.[3] Instead, capture an ultrasound clip, resume CPR, and then review the clip.

Check out our video on POCUS in cardiac arrest by Dr. Christina Wilson

The Structure

The time to figure out your steps in a cardiac arrest resuscitation is not when the patient hits your door. Preparing for the arrest patient ahead of time is crucial. Here is Salim’s structure and steps to running a code in the community. Recognize these are the steps in order of priority, they often happen simultaneously.

Prioritization of Code

CPR & early defibrillation should always be the priority.

I prefer a LUCAS Device in the community, as I don’t have the man or woman power to continue compressions.

Apply defibrillator pads.

Obtain venous access – I prefer bilateral humeral IO's. These are 15 g needles and close to the central circulation.

Insert a laryngeal mask airway (LMA) unless there is return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) at which point I would intubate (be careful not to over ventilate which can ↑intrathoracic pressure and ↓venous return).

End Tidal CO2 (EtCO2) – EtCO2 helps to quantify your quality of compressions, as numbers < 20 are thought to represent inadequate perfusion. This is not an exact science as LMAs do not create a closed loop, but this is a nice surrogate of how compressions, etc. are going. Significant drops in EtCO2 can signify poor compressions while a significant increase may be your first sign of ROSC.

POCUS can help identify any reversible causes (eg. tamponade) and assess for cardiac activity. Using the phased array probe in the subxiphoid view, record what you are doing so you can look at it without causing prolonged CPR pauses. Echo also helps distinguish between PREM & PRES (Pulseless Rhythm Echocardiographic Motion & Pulseless Rhythm Echocardiographic Standstill) in PEA – the first is profound shock, the second is true PEA…this distinction is important as the former needs pressor support and the latter needs CPR.

Start an epinephrine drip.

The Epi Drip Parameters

Start with EtCO2 … it isn't great, but it gives you a rough estimate

If EtCO2 < 20 mmHg, you need to optimize your CPR and give 1mg epi bolus followed by epi drip

If EtCO2 > 20 mmHg just start a low dose epi drip

Ideal asessment is via an arterial line

Maintain DBP > 25 mmHg (AHA recommendations), some argue to aim for 35 - 40 mmHg

How Salim does it:

If DBP < 35mmHg optimize CPR and give 1 mg epi bolus followed by epi drip

If DBP > 35mmHg just start low dose epi drip

PEA Approach

Some have proposed a narrow vs wide complex approach to PEA.[4] This is based off a paper in 2014 by Littmann, who proposed a structured approach meant to replace the commonly used Hs and Ts.[5] As Salim points out in the interview, this approach may not be as consistent or effective as originally thought.[6]

Collectively, many believe ultrasound is the key to figuring out PEA - and specifically differentiating two subtypes of PEA- PRES and PREM as noted above. Some call this PEA vs pseudo-PEA which is really profound shock.[7] The bedside echo is very instrumental here.

References:

1. Cunningham LM, Mattu A, O'Connor RE, Brady WJ. Cardiopulmonary Resucsitation for Cardiac Arrest: The Importance of Uninterrupted Chest Compression in Cardiac Aresst Resuscitation. Am J Emerg Med. 2012 Oct;30(8):1630-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.02.015. Epub 2012 May 23. [https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0735-6757(12)00096-4]

2. Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, et al. Part 8: Adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2010;122(18 suppl 3):S729–S767. [pdf]

3. Huis In 't Veld MA, Allison MG, Bostick DS, Fisher KR, Goloubeva OG, Witting MD, Winters ME. Ultrasound use during cardiopulmonary resuscitation is associated with delays in chest compressions. Resuscitation. 2017 Oct;119:95-98. [Pubmed]

4. Littmann et al. A Simplified and Structured Teaching Tool for the Evaluation and Management of Pulseless Electrical Activity. Med Princ Pract 2014; 23: 1 – 6. [Pubmed]

5. Kloeck WG. A practical approach to the aetiology of pulseless electrical activity. A simple 10-step training mnemonic. Resuscitation. 1995;30(2):157–9. [Pubmed]

6. Bergum D, Skjeflo GW, Nordseth T, Mjølstad OC, Haugen BO, Skogvoll E, Loennechen JP. ECG patterns in early pulseless electrical activity-Associations with aetiology and survival of in-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2016 Jul;104:34-9. [Pubmed]

7. Pulseless electrical activity on Life in the Fast Lane

8. Evidence based pearls for the management of cardiac arrest by Dr. Andrew Perron