Journal Club - Emergency Department Initiated Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder

/Background

Recent data from the National Center for Health Statistics reveal that in the 12-month period ending in April 2021, more than 100,000 Americans died of an overdose, a staggering increase of nearly 30% the prior year. While the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to overdose deaths and taxed constrained Emergency Department (ED) resources, it has also clarified the important role that emergency physicians have in expanding access to life-saving medications to treat opioid use disorder. In this journal club, we review the evidence on ED-initiated buprenorphine, including barriers to implementing ED-buprenorphine here in rural Maine.

Articles reviewed

1. D’Onofrio, et al. Emergency Department-Initiated Buprenorphine/Naloxone Treatment for Opioid Dependence: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015; 313(16):1636-1644.[Pdf]

2. Rosenberg, et al. Barriers and facilitators associated with establishment of emergency department-initiated buprenorphine for opioid use disorder in rural Maine. The Journal of Rural Health. 2021; 1-8. [Pubmed]

3. Herring, et al. High-Dose Buprenorphine Indication in the Emergency Department for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder. JAMA Network Open. 2021; 4(7): e2117128.[Full text]

Additional reading

4. Hawk, et al. Consensus Recommendations on the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder in the Emergency Department. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2021; 78(3): 434-442.[Pdf]

D’ONOFRIO ET AL

In this important study, D’Onofrio and colleagues randomized 329 opioid-dependent ED patients to one of three groups:

Screening and referral to treatment (referral, n = 104)

Screening, brief intervention, and facilitated referral to community-based treatment services (brief intervention, n = 111)

Screening, brief intervention, ED-initiated treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone, and referral to primary care for 10-week follow-up (buprenorphine, n = 114).

The primary outcome was enrollment in and receiving addiction treatment at 30-days post-randomization. Additional outcomes included self-reported days of illicit opioid use, urine testing for illicit opioids, HIV risk, and use of addiction treatment services. 329 participants were enrolled at an urban teaching hospital over a period of four years.

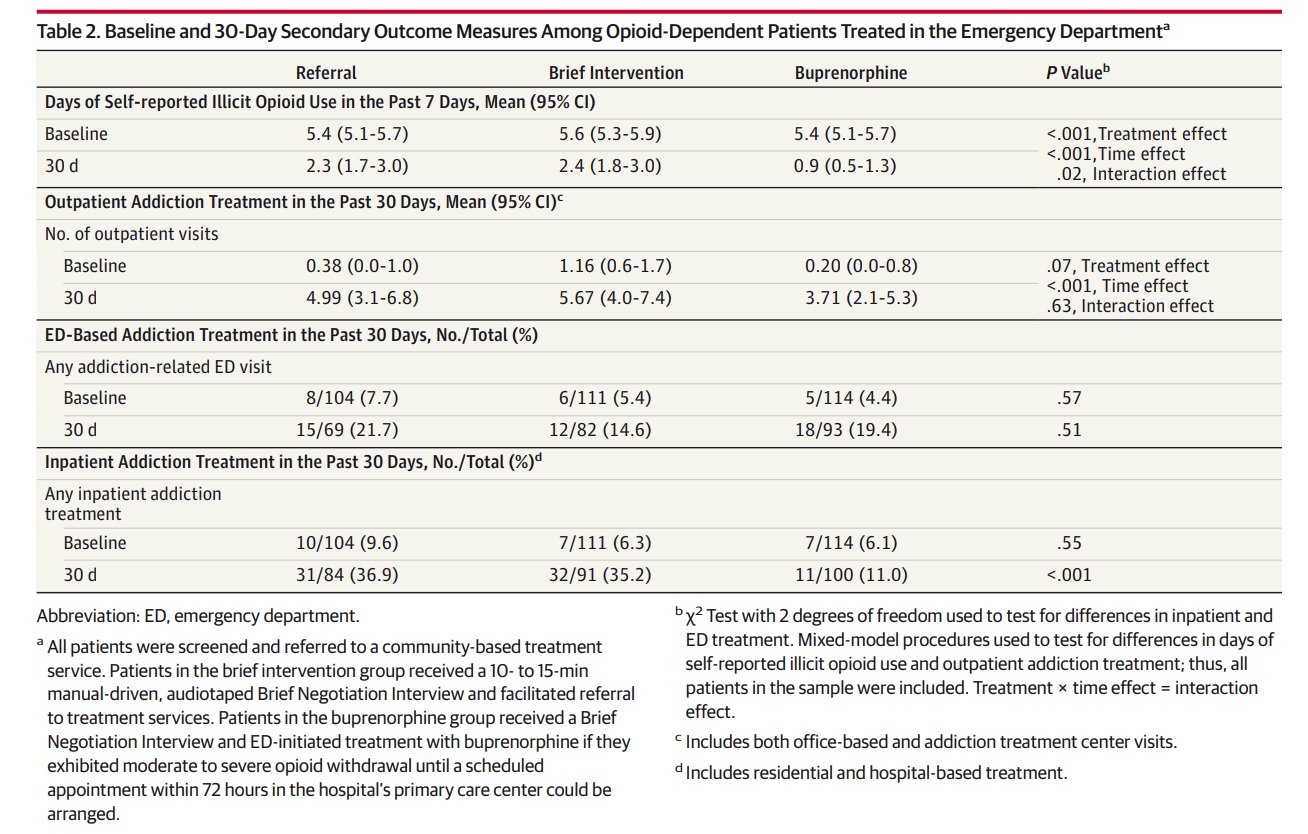

78% of participants in the buprenorphine group (89/114, 95% CI: 70-85%), 37% of participants in the referral group (38/102, 95% CI: 28-47%), and 45% of participants in the brief intervention group (50/111, 95% CI: 36-54%) were engaged in addiction treatment at 30 days (p < 0.001). In addition, those in the buprenorphine group demonstrated decreased rates of inpatient addition treatment utilization and self-reported days of illicit opioid use (see Table 2). Urine samples testing positive for opioids and HIV risk did not differ significantly amongst the groups.

Bottom Line: Among adult opioid-dependent patients, this study provides evidence that ED-initiated buprenorphine, compared with brief intervention and referral, significantly increased engagement in formal addiction treatment, reduced self-reported illicit opioid use, and decreased use of inpatient addiction treatment services but did not significantly decrease rates of positive urine testing for opioids or HIV risk.

ROSENBERG ET AL

Northern New England and, in particular, Maine have been especially hard-hit by the opioid epidemic, with Maine experiencing its’ highest number of opioid deaths ever in 2020. Despite this, implementation of ED-initiated buprenorphine programs has been slow across the state, particularly in rural locations.

Rosenberg and colleagues took a qualitative approach when investigating barriers and facilitators to successful implementation of ED-initiated buprenorphine programs in critical access hospital EDs across Maine. They conducted semi-structured interviews (n = 11) with ED directors across Maine using an interview guide designed to elicit responses around the reasons for starting or not starting and ED-buprenorphine program as well as barriers and facilitators to ED-based buprenorphine. The interviews were conducted and recorded via Zoom and the recordings were then transcribed verbatim for analysis. The investigators used thematic analysis to independently code transcripts using an initial set of deductive codes, followed by inductive codes developed during the coding process. All transcripts were then coded using a final code book and resultant codes were organized into themes and subthemes with supportive quotes.

Four major themes (compelled to act, leadership and mentorship, stigma and outreach and follow-up) and 11 subthemes were identified (see Table 1). Findings revealed that individual physicians’ motivation from personal experiences with OUD and supportive hospital leadership were important in supporting development of ED-buprenorphine programs. Mentorship and knowledge-sharing between ED directors was also helpful. Barriers included overcoming stigma from hospital staff, developing community outreach, and obtaining appropriate follow-up for patients.

Bottom Line: ED directors’ clinical experiences with OUD patients, supportive hospital leadership, and peer mentorship all facilitated ED-buprenorphine programs in rural Maine EDs. Overcoming stigma, developing community outreach, and obtaining appropriate sources of follow-up for patients were important barriers. These findings may be helpful for other rural EDs considering starting an ED-based buprenorphine program.

HERRING ET AL

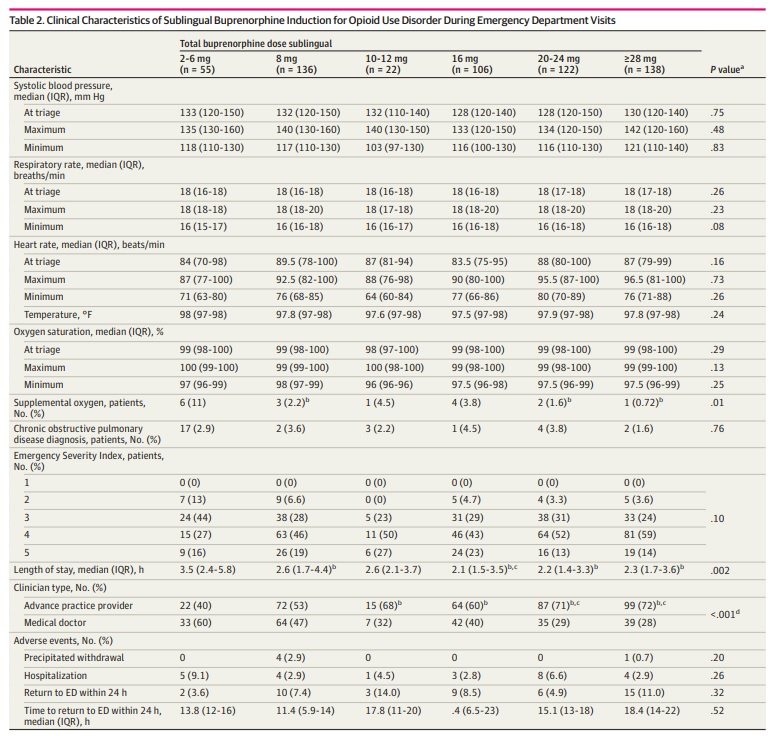

As the potency of the illicit drug supply increases, emergency physicians have increasingly used a high dose (>12 mg) strategy for ED-initiated buprenorphine induction to achieve adequate agonist blockade and suppression of opioid withdrawal and cravings. In this retrospective case series, Herring and colleagues examined the safety and tolerability of high dose (>12 mg) buprenorphine induction for OUD patients presenting to the ED.

They examined electronic health records for 391 patients who had been treated in their ED using a high-dose (more than 12 mg and up to 32 mg) buprenorphine pathway (see Figure 1). Outcomes included the occurrence of precipitated withdrawal and any other serious adverse event attributable to buprenorphine administration including sedation, decreased respiratory rate, hypoxia, or rescue naloxone administration in the ED or within 24 hours following discharge.

Among 391 unique patients, a high dose of buprenorphine (>12 mg) was administered during 366 encounters (63.2%) including 138 doses (23.8%) that were ≥ 28 mg (see Table 2). No cases of respiratory depression or sedation were reported. Five cases (0.8%) of precipitated withdrawal were identified, but had no association with dose – four cases occurred after an 8 mg buprenorphine dose. Three serious adverse events unrelated to buprenorphine were identified (diabetic ketoacidosis, myocardial infarction). Nausea or vomiting occurred infrequently (2-6% of cases).

Bottom Line: Findings from this retrospective study of a prospectively implemented high-dose ED buprenorphine pathway suggest that high-dose buprenorphine induction is safe and well-tolerated in patients with previously untreated opioid use disorder. Further prospective study in settings with clinicians who do not have as much ED-induction experience is warranted, as is study with buprenorphine formulations that include naloxone.

There is strong evidence supporting the safety and efficacy of ED-initiated buprenorphine for ED patients with untreated opioid use disorder.

The American College of Emergency Physicians recommends that emergency physicians offer to initiate opioid use disorder treatment with buprenorphine in appropriate patients and provide direct linkage to ongoing treatment for patients with untreated OUD.

For patients with high opioid tolerance, continued withdrawal symptoms after initial dosing, or factors that limit access to buprenorphine prescription following discharge, high dose buprenorphine induction in the ED may be a safe and well-tolerated option.

While barriers to implementing an ED-based buprenorphine program exist, particularly in rural locations such as Maine, strategies such as capitalizing on physicians’ personal experiences with OUD, supportive hospital leadership, and mentoring and information-sharing between ED directors helps nurture program development.

Download article summaries

Authored by Tania Strout, PhD, RN, MS, Heidi Roche MD, Jennifer Mabey MD, Zach Tillet MD

Edited and Posted by Jeffrey A. Holmes, MD